Courts have stolen almost 10,000 years from Black people wrongfully convicted of crimes and later exonerated. This figure represents only known cases of wrongful convictions. The actual number is likely much higher.

Source: National Registry of Exonerations

Articles published on racism in the American legal system eventually reach the same conclusion– White justice and Black justice (or Brown, LGBTQ justice or what passes for justice if you are anyone labeled “other”) are not the same. The lack of racial diversity in the legal profession is often cited as part of the problem. In deed, the judiciary, one of the three pillars of democracy in this country, has failed to achieve levels of racial and ethnic diversity that create the “critical mass” (when sufficient numbers of non-White lawyers, judges, paraprofessionals or staff are present in a majority White dominated setting to create sustainable progressive change through collective action) necessary to counter the forces of White supremacy within the legal profession .

A chart of demographic trends prepared by the American Bar Association (ABA) shows the national percentage of White attorneys in the profession decreased only slightly over a 10-year-period. In 2008, White lawyers were 89% of the legal profession. This number dipped to 85% in 2018. The lack of racial diversity is even starker when looking at the national demographics for elected prosecutors, 95% who are White. Not only is there a glaring racial imbalance among prosecutors, there is also one among state court judges. A report released by The American Constitution Society for Law and Policy (in June 2016) revealed the nation’s judges, too, are overwhelming white—in fact, 80% of all state judges are White (58% White men and 22% White women.) When 90% of all cases in the United States are tried in state courts, this racial and ethnic “gavel gap” suggests the much touted notion of color-blind justice is little more than a legal fiction.

Rule 8.4 (comment 3) of the Model Rules of Professional Responsibility imposes ethical restrictions on the use of words or actions reflecting racial bias or prejudice but it is a lawyer’s individual conduct not his/her complicity in helping to perpetuate and maintain a racist justice system that triggers scrutiny and possible discipline. A position that ignores what study after study has documented– mainly racism is systemic and operates in one form or another at every stage of the criminal punishment process.

In Arizona where the African-American population is 4% of the general population but 12% of the prison population and where the state’s incarceration rate of Black defendants is 6th in the nation, evidence of pervasive anti-Black bias within the criminal punishment system has been largely overlooked. A 2017 report on drug sentencing in Arizona prepared by the American Friends Society Committee (AFSC) found “significant racial disparities in drug sentencing.” Specifically, data collected from the Arizona Department of Corrections (ADOC) showed Black defendants convicted of drug offenses received sentences 25% longer than defendants from other races and ethnicities convicted of the same crimes. However, these findings had no impact on how Black drug defendants were sentenced in the Pima County Superior Court. No moratorium on drug cases involving Black defendants was ordered by the Courts or requested by prosecutors–the racially biased drug sentencing continued unabated and continues even now. The American Civil Liberties Union (ACLU), whose Arizona chapter refused to advocate on behalf of Black defendants serving longer prison sentences because of their race, recently issued a report on mass incarceration in Arizona (released September 2018) acknowledging racial bias is so deeply ingrained in the state’s criminal punishment system, new approaches for mitigating the causes of these racial disparities are needed.

In fact, what is needed are not merely criminal justice reforms calling for the election of progressive prosecutors or proposals to enact new reform legislation but rather the will to make strategic structural changes in order to shift power from system insiders to those communities most impacted by decades of mass incarceration policies. What is needed are lawyers willing to reject the status quo because it requires them to be silent and worse, to be complicit with a system they know is rooted in White supremacy. What is needed are more Courts with the moral fortitude to speak hard truths about the racism within the justice system like the Washington State Supreme Court did when it declared last week (October 11, 2018) the state’s death penalty was unconstitutional because it was ” arbitrary and racist.” What is need quite simply is more transformative justice.

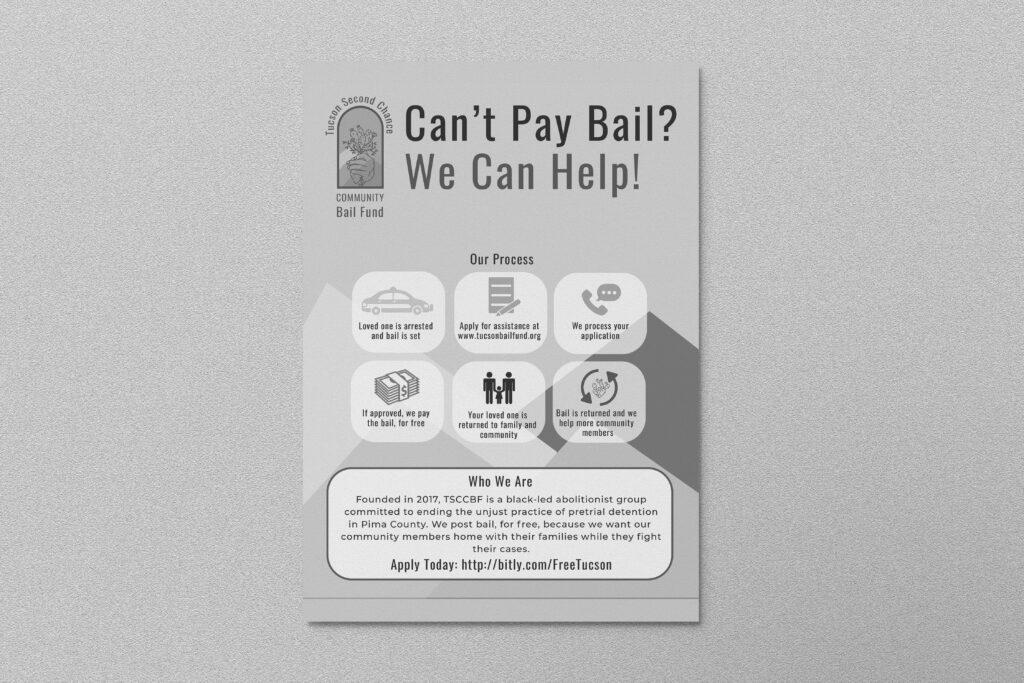

Need to request help? Download our community application flyer or visit our Request Help Page to submit an applicaton!